Reading time: 25 min

[Written on the 18th of January, 2021]

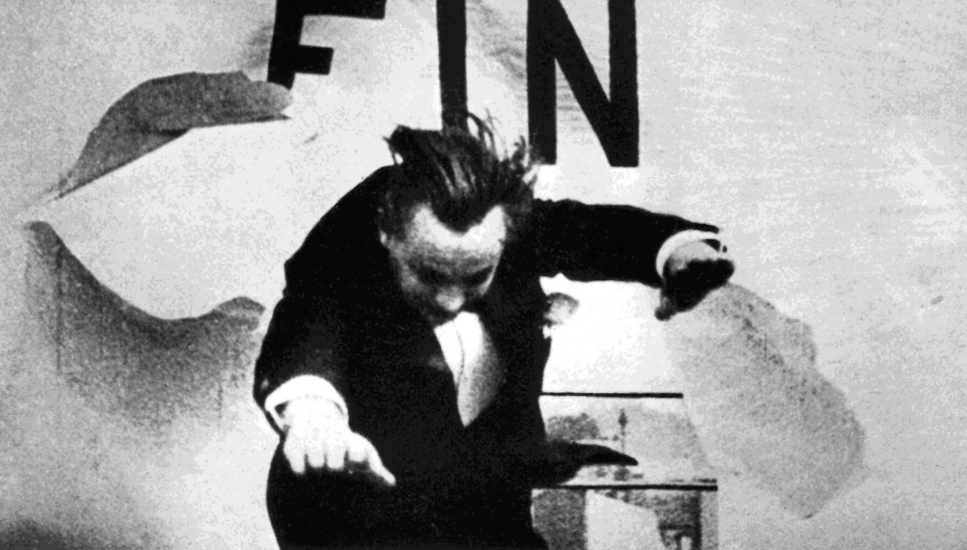

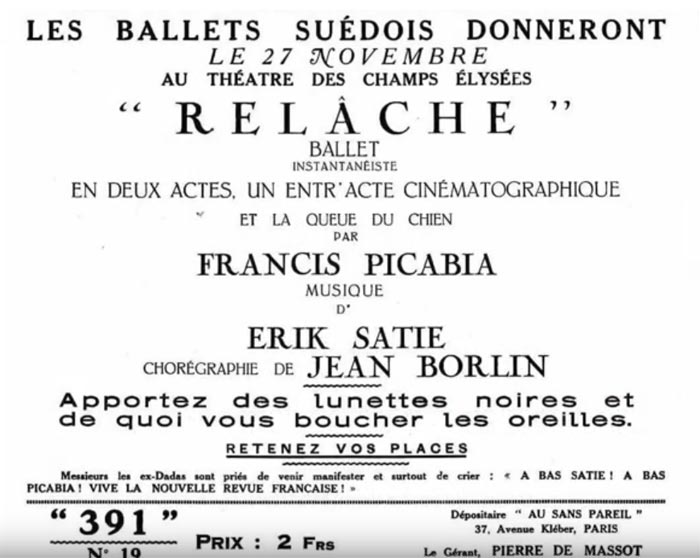

(Entr’acte by René Clair and Relâche by Francis Picabia)

René Clair’s Entr’acte (1924) and Francis Picabia’s Relâche (1924) are two works that were made to be presented together: the former was an experimental intermission film that segmented in two acts the latter, an unusually provocative and humorous ballet show. The experience as a whole links in many ways to the Dada movement, but what exactly points to that? In this article, I will break down an understanding for the Dada aesthetic in order to accordingly study both Clair and Picabia’s pieces and conclude that, through their experimental forms, convention-breaking identities and use of subversion to tackle complex social-political notions, these two pieces represent exactly what we can call Dada Art.

The Dadaist movement represents a variety of complex notions and intricate point of views across Art and the different artforms that exist, but it is the core of the movement that is important to consider here. Dadaism began as a result of European artists starting to reject certain societal ideas within the capitalist system of the time. For example, they didn’t believe in the concepts of ‘reason’, ‘logic’ and, intriguingly, ‘aesthetic’ at all, instead they embraced the ‘irrational’, ‘absurd’ and ‘humorous’ to protest against reality. A great first example of this is Tristan Tzara, the considered founder of Dada, who wrote an ‘anti-manifesto’ manifesto in 1918.

It could therefore feel somewhat ironic to contemplate the idea of aestheticism in relation to Dadaism. This said, it is critical to understand that the movement does have an aesthetic identity which precisely lies in its non-aestheticism. As enigmatic as this sounds, this notion seems to have stemmed from a key idea: ambiguity. Elizabeth Benjamin’s book ‘Dada and Existentialism: The Authenticity of Ambiguity’ and Hanne Bergius’s article ‘The Ambiguous Aesthetic of Dada’ are two works that helped me begin unpicking these ideas.

On the one hand, Benjamin talks about ‘ambiguity’ in relation to the ‘multifaceted interpretability’ of Dada artworks and the ‘merging of realities’ that takes place within them.

By proposing a philosophical view on Man Ray’s film ‘Le Retour à la Raison’ (1923), Benjamin casts light on the filmmaker’s work on perception, an idea that she relates to Sartre’s view on the construction of human perception that ‘no group of objects is particularly designed to be organized as ground or as figure: everything depends on the direction of my attention’. Thus, in the same way non-Dadaist artworks are crafted to point to certain ideas, messages or present particular aesthetics, Dadaist artworks embody the artists’ conscious effort to form uncertainties in order to create a ‘deliberate misdirecting of attention’, which then ultimately leads to an unlimited number of interpretations.

For Benjamin, the ambiguity also lies in the Dadaist artworks’ ability to place the audience’s ‘perception into a state of simultaneous position of presence and absence’. This is fundamentally linked to the question of reality, and in this case, she contemplates the relationship of dream and reality with regards to, in fact, Clair’s Entr’acte (1924). Indeed, with at its root craftwork and montage, the notion of the ‘merging of realities’ is a true quality of Dada Art – whether it is in newspaper collage works, unusual ways of writing poetry or more specifically in the layering of shots of slanted roofs and buildings in Clair’s film. Overall, all pieces seem to do a similar thing: lead our perception in one way or another into questioning what is real, but also more simply what is there and finally what is true. One might even suggest that this ‘reality merging’ could help hint to perhaps, the Dadaists’ true feelings about their perception on reality itself. Thus, although Dadaists produce work in many extraordinary and unusual manners, Dadaism might have also just been a way for artists to desperately get attention from society in order to spark social-political change, which was the movement’s initial motivation, reminding us that Dada artists, like any other artists, are human before anything else and, in existentialist Sartre’s words, ‘condemned to be free’.

On the other hand, Bergius seems to first root ‘ambiguity’ in the time era when Dadaism began – she notes the Baroque Age -, when ‘men became interested in sense-deception’. Later, she attributes the ambiguity to the Dada artist’s ‘desire to negate and synthesize’.

For Bergius, the start of the twentieth century, with the development of media outlets that told stories that were ‘factually real’, caused for precisely what the Dadaists contemplated in their art: the dichotomy reality vs the reality of illusion. It isn’t shocking to think that a sudden and gigantic wave of ‘validated facts’, from numerous sources, could overwhelm people, causing them to reflect more on what they read, the notion of truth, as well as their own realities. Thus, in response to that, some people might have begun to ask themselves the following: ‘Is reality simply what I decide to tell it is?’ In many ways, this could be compared to today’s fake news. Moreover, while no one can ever be all-knowing, the arrival of this type of news constructed a belief that people could know way more real and factual information than they ever could imagine – but the issue is the following: real to who and why is it even important? This is what Dadaism seems to be questioning.

Then, as Bergius describes, the Dadaists make an effort to de-compose and nullify the world in order to unify old ideas in a playful and irrational fashion, proposing what could be described as the most real ‘non-real and anti-Art’ Art that exists. The ambiguity here lies in the intentions, like in the end result, because it is precisely ‘ambiguity’ that fuels Dadaism throughout. In addition to this, Dadaism engages with profound dualisms that puts in relation opposites that purposefully create ambiguity: Art that has an ‘anti-structure’ structure, an ‘anti-message’ message, an ‘anti-aesthetic’ aesthetic… at a time in the world where, in Bergius’s words, ‘reason gave rise to its own madness’ and Dada artists fought this madness with more madness. Thus, I believe it is fair to claim that the Dadaists were the most desperate playful artists.

Overall, in this light, the notion of ‘ambiguity’ plays a fundamental role in Dadaism and more precisely in the Dada aesthetic, which doesn’t exactly have the same criteria as other Art movements, but rather embodies the entirety of the unlimited scope of artistic directions that exist in Dada Art. Through its different manifestations across artworks and theories, ‘ambiguity’ therefore characterizes Dada Art as at once sporadic but precise, non-uniform but consistent, rule breaking but following particular guidelines, ‘present and absent’ and at core aesthetically non-aesthetic.

Clair’s Entr’acte was a film made to complement Picabia’s ballet Relâche that reflected the ballet’s attitude and motivations as a piece with a peculir non-aesthetic aesthetic. Entr’acte proved at once the potential of the cross-mediatizing of Dadaism and furthermore flexed the power behind a subjective or individualistic artistic approach – in the way another existentialist Albert Camus would suggest: ‘I rebel, therefore we exist’ – through purposeful experimentation with the medium of cinema.

Entr’acte embraces the Dada aesthetic through what Noël Carroll calls ‘its contempt and disdain for the bourgeois version of culture’. The film’s experimentative and absurd nature could be thought to spark directly from Clair’s rejection of conventional values and structures, which naturally resulted in novelty and innovation in his piece. While an Art Cinema perspective might argue that experimentation is not always Dada, the coupling of experimentation with the very bourgeois subjects in his film point clearly in the direction that Carroll describes. It could therefore be considered that everything that constitutes this film, like the overall Dada aesthetic, is everything that precisely does not constitute non-Dada Art. Thus, Entr’acte demonstrates that creative possibilities within Dadaism are truly endless. This said, in light of Clair’s experimentation, there are three main pillars that particularly show this: montage, narrationand mise-en-scène.

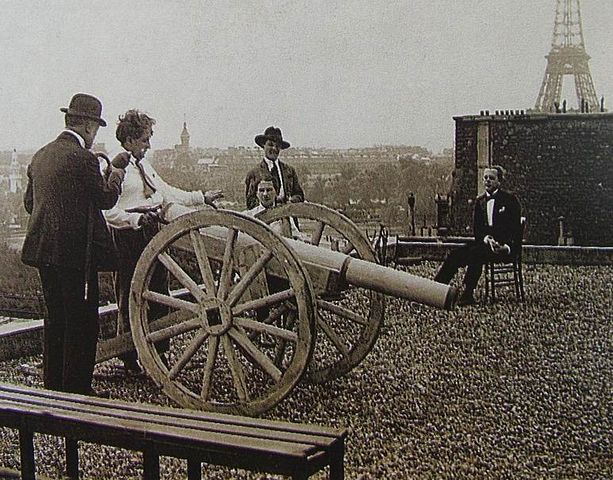

First, the montage is most noticeable. The montage is fast-paced, the editing juxtaposes and overlays different shots of people, objects and locations in relation to one another to create new meanings. There is also the use of special effects and illusions, and the use of music increases or alleviates tension throughout. For example, the scene where a man is trying to shoot at a levitating egg is indicative of this. The film cuts back in forth between the egg and an armed man on a rooftop, but there are also shot inserts of the ocean, another armed man on a rooftop, a flying bird, a target…etc, and this, for about two minutes in a quick and organized edit. At one point, the egg, that is either levitating or in the air, perfectly balanced under the jet of a water fountain, duplicates itself multiple times using an overlay effect, but also slow motion. This could be interpreted in different ways: either showing the man’s hallucination as he focusses on his shot, or the man’s confusion at the illusionistic sight of a dozen ‘flying’ eggs. The truth is no one truly knows. If considered in relation to the Kuleshov effect, this scene becomes increasingly voyeuristic – a game of who is watching who or what. Finally, this scene elegantly sways between the notions of tension and contemplation with the use of a score that complements the visuals and emphasizes the emotion. Quite shockingly, this scene ends with the first armed man being shot dead by the other man, thus falling off the building onto the street, where a crowd is already gathered for his funeral.

Secondly, the narrative is in nature non-existent, although the sequencing of the scenes creates a followable train of events. Indeed, the montage enables for the telling of an unusual story that doesn’t follow traditional codes of narrative structure. Carroll notes the following:

By subverting narration in Entr’acte, Clair not only involved himself in an attack on an artistic institution, but also in an attack on the most customary practice of rational thought in bourgeois culture.

Therefore, Clair could be thought of making a case for yet again, doing the opposite of what bourgeois culture would do (the -anti) in a sign of protest. Regardless, in his narration, the ‘absurd’ takes over the ‘rational’. This said, there is a clear structure for a narrative, only this one isn’t exactly representational of reality as it presents itself, or the one we seem to know. Rather it is a narrative that seems to follow the lines of train of thought and human thinking more closely, resulting in creating a deeply introspective piece. This is a typical attribute of Dada Art, for it does seem to focus on structure as a means to an end, but rather it focusses on not focussing on structure in order to open up to the deeper and greater potential of narration and narrative interpretation.

Finally, the mise-en-scène is not uniform at all. Although, there are real actors’ performances, art direction, use of different locations and a certain score… one can’t help to recognize how exceptionally free the mise-en-scène seems to be overall. On the one hand, the film is full of conventional (silent) film-like scenes with for example, one real-life subject like the ballet dancer, or two subjects like the two men talking next to the canon, or a group of people like the bourgeois men and women waiting in line at the funeral behind the carriage. Indeed, the framing and the shot structures are pretty common. In many of them, they embrace the new, but not unheard of, techniques of filmmaking like the close-up, the wide shot and the panning shot. Furthermore, these performances always resemble reality, or theatre in the most expressive scenes. However, they are not absurd or irrational at all if viewed independently and evaluated at face value. On the other hand, the film is full of random, unexplainable and surprising elements of mise-en-scène: the funeral attendees jumping up and down in unison following the carriage, the man on a rooftop shooting at a flying egg, the carriage taking control of itself and riding down the street, a thought-to-be dead man coming back to life…etc. Moreover, the shots of the ballet dancer filmed from under her and showing up her skirt, or the inflatable balloon head dolls riding on a train, are enough to showcase the other type of mise-en-scène that takes place in this film. They are these more curious passages that bring in the notions of absurdity, irrationality and questioning for the viewer. Thus, thanks to the montage, Clair juxtaposes particular scenes with specific mise-en-scène to create conflict, build tension, spark uncertainties in the narration, all the while being true to cinematic forms and conventions on one side and true to experimental film on the other. It is through the merging of ‘realities’, in other words the juxtapositions between types of mise-en-scène, that Clair creates at once a clustered and vibrant piece and overall shares the feeling of absolute artistic freedom with his work.

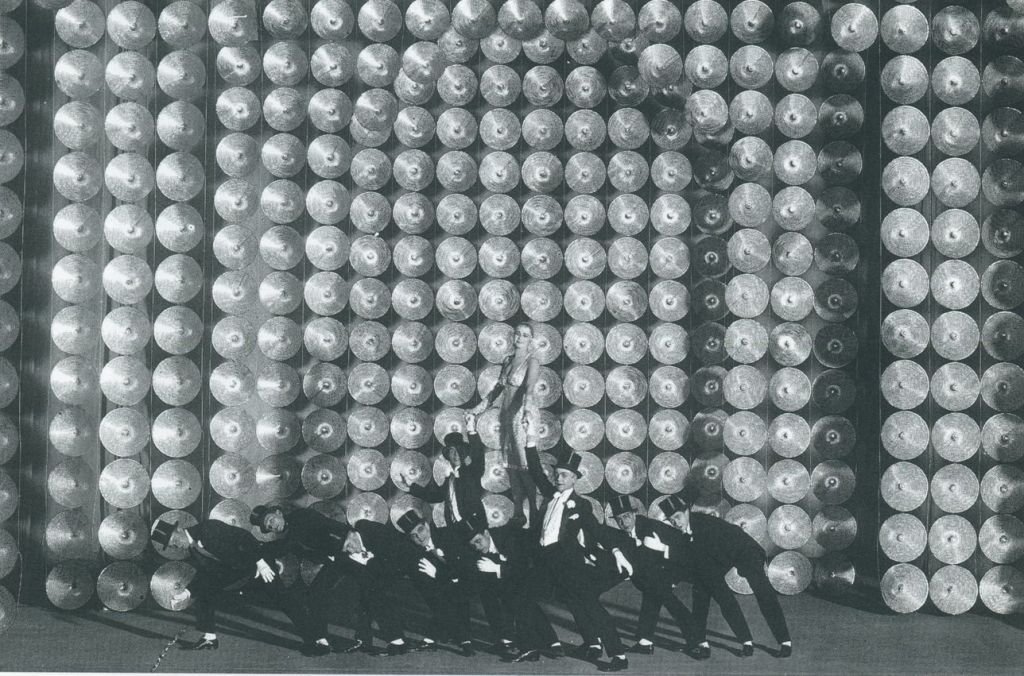

Almost as expected, Picabia’s ballet Relâche generallyshares a similar aesthetic to Clair’s film, however its live and performative nature makes the show particularly provocative and humorous. Unlike Entr’acte, it possesses the qualities of the ‘real’ and the ‘live event’ in a way that only pure theatrical performances could match. Karine Bouchard’s commentary on the history of the performing arts and on Dada is interesting to consider in this context:

[…] l’histoire de la scène – qui appartient moins aux arts de l’espace que ceux du temps – et l’histoire de Dada – qui se sent moins concernée par le film – ne tiennent pas un discours interdisciplinaire […]

Through the scope of History of Art, Bouchard explains that on the one hand, the history of the performing arts is more concerned with the notions of time than space, and on the other hand, the history of Dadaism has not exactly been most represented through film. Thus, she then presents her belief that both histories do not hold any interdisciplinary discourse with one another. One could interpret this in separate ways but, in this case, the idea could be viewed to contradict the prominence of Dada aesthetic in Relâche as the ballet’s conceptual and visual proximity with Clair’s film might be greater than its own link with the history of Dadaism. Therefore, it might be critical to consider Relâche more literally here. More so comparing it to the history of the performative arts than with the history of Dadaism (or what it has been characterized as). Thus, one can first focus on how the ballet single-handedly breaks all conventions of performative arts, before then linking it to the Dada history.

The ballet can be perceived as particularly provocative because it bends the conventions of performative arts to interact (in)directly – through the absurd – with the spectator who is in the same room. Indeed, it seems to be the idea of proximity, at once physically and therefore then mentally, that makes the experience unique and particularly resonant for the viewer. In fact, the spectators become part of the show. In view of this type of performance, the notion of time becomes a real character for the spectator, as spectators can wonder in confusion at the sight of such a show. This enhances the cathartic nature of the ballet as the spectator experiences irrationality with their own eyes and for a duration that is beyond their control. In contrast, where Clair’s Entr’acte achieves to suggest similar ideas through a new approach to film, the nature of Picabia’s Relâche make it very hard to resist a full experience. Indeed, instead of merging realities through layering and montage, the performance enters and invades the spectator’s true perception of reality. One could argue that this is precisely what ‘provocation’ is made of. Moreover, one could identify two grounds of provocation in Relâche. On the one hand, it can take place literally in an anecdotical fashion: for example, at some point in the ballet, a female lead dancer can be seen pushing a wheel barrow on stage, or another pair of female dancers can be seen wearing nurse uniforms but with red crosses covering their breasts. Particular moments or attitudes go against the grain and can provoke an audience. On the other hand, it can birth from the accumulation of convention breaking elements mixed with the very nature of the medium of the performative arts, where spectators lack in control over the piece. Both of these sides add to make Relâche a challenging experience and a particularly confusing piece. Thus, by re-establishing the spectator’s ‘real’ reality with the notion of the ‘absurd’ for the duration of a show, the ballet creates an unsettling experience and sends a message to society, similarly to how Hugo Ball’s poetry reading at Cabaret Voltaire in 1916 marked the beginning of Dada poetry.

Secondly, humour is anchored in the aesthetics of Relâche. More specifically, humour lies in Picabia’s ability to make Relâche a self-mocking piece. Oliver C. Speck links humour in Dadaism to the determining of ‘seriousness’:

The point of differentiation between serious art with the mission to subvert and ‘joke’ art, lacking this mission, concerns precisely the humouristic context. The question – ‘Is this serious?’ – decides if the artwork is ‘really’ subversive or ‘just a clever joke’.

In this light, there is no doubt that Picabia’s ballet, like Clair’s film, are subversive pieces. In Relâche, there are humorous elements that spark from the absurd costumes, bizarre choreography, incomprehensible actions but more generally, it might be Picabia, Erik Satie (music), Clair and the performers’ seriousness towards the show itself that creates the humorous quality for the common spectator. Maybe does the ‘Is this serious?’ question spark more from a place of pity than confusion. Moreover, Relâche becomes at once the source and the target of mockery because, for this particular type of spectator, nothing makes sense and everything is just foolish. As previously stated, the Dada aesthetic embodies the notion of the -anti, but also the notion of subversion. Furthermore, one could argue that in the context of humour, the Dada concept of ‘destroying in order to rebuild’ takes place within one’s self. It seems that with humour, Relâche specifically frees itself from social expectations and instead embraces the opposite: a mix of social provocation and childish playfulness in order to precisely subvert reality for itself. Thus, by not taking themselves seriously (although they were very serious), the Dadaists developed a safe way to subvert conventions by making it look like they were laughing at themselves although it is clear that they were laughing at the world. Maybe this is what Tristan Tzara was contemplating when he claimed that ‘Thought was made in the mouth’.

Clair’s Entr’acte and Picabia’s Relâche are very insightful pieces for the understanding of the Dada aesthetic. Although they mostly present the complexities that come with this study, both pieces show, through their profound ambiguity and apparent non-aestheticism, that their aesthetic identity is the result of purposefully mixing subversion and technical experimentation together. In Clair’s Entr’acte, one could argue that the specific montage, narration and mise-en-scène are the defining elements of the film’s aesthetics. In Picabia’s Relâche, one could suggest that the mixing of provocation with humour embodies the ballet’s aesthetic nature. Overall, both pieces show that the Dada aesthetic is non-uniform and bound to no specific rules. Both pieces show that the Dada aesthetic is inherently linked to the idea of using Art to ‘oppose’ but without conflict, or in other words to subvert but with nothing else but creativity and inventiveness.

Bibliography and filmography:

Clair, R. (Director). (1924). Entr’acte [Motion picture]. France: Société Nouvelle des Acacias.

Lorraine, C. (2021, January 16). RELACHE (1924), Reprise 2014 – Petter Jacobsson et Thomas Caley – Francis Picabia © ADAGP, Paris 2014. Retrieved January 18, 2021, from https://vimeo.com/96056059

Benjamin, E. (2018). ‘Dada and existentialism’. In ‘Dada and existentialism: The authenticity of ambiguity’. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. (pp. 65-66).

Bergius, H. (1979). ‘The Aesthetic of Dada’. In ‘The Ambiguous Aesthetic of Dada: Towards a Definition of its Categories’ Journal of European Studies, 9 (33-34), (pp. 27-28).

Carroll, N. (1977). ‘Entr’acte, Paris and Dada’ Millennium Film Journal; Winter1977/1978, Vol. 1 Issue 1 (p.6, p.8).

Bouchard, K. (2009). 2.2.2. Relâche: L’histoire de Dada et les monographies d’artistes. In Les relations entre la scène et le cinéma dans le spectacle d’avant-garde: Une étude intermédiale et in situ de Relâche de Picabia, Satie et Clair (p. 32).

Speck, O. C. (2009). The Joy of Anti-Art: Subversion through Humour in Dada. In G. Pailer (Author), Gender and laughter: Comic affirmation and subversion in traditional and modern media (p. 372). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Kłos, A., & Says:, 8. (2016, May 27). Dada as a worldview – Dada 100 Years. Retrieved January 18, 2021, from https://retroavangarda.com/dada-as-a-worldview/

A quote by Jean-Paul Sartre. (n.d.). Retrieved January 18, 2021, from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/5012-man-is-condemned-to-be-free-because-once-thrown-into

Tristan Tzara Quotes (Author of Seven Dada Manifestos and Lampisteries). (n.d.). Retrieved January 18, 2021, from https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/45688.Tristan_Tzara